The Trump administration’s new trade tariffs on Canada come as a surprise, given their inflationary impact and the stark differences between Canada and China. While the move aligns with Trump’ broader economic nationalist agenda, it may be more symbolic than strategic, argues Christian Dippel, Ivey Professor and LNC faculty fellow. In this perspective piece, Dippel explores the political motivations behind the tariffs and presents six key reasons why U.S.-Canada trade relations are likely to normalize sooner than expected. From Trump’s negotiation style to economic realities like the Triffen Dilemma and inflation concerns, benefits to the US from lasting tariffs are weak—suggesting that trade stability will return well before CUSMA’s renewal in 2026.

The Unexpected Tariffs on Canada

When the first Trump administration went after trade with China in early 2017, that move was easy to understand. While most economists disagreed with the tariffs, it was easy to see the political rationale: by 2016, there was a strong empirical consensus in economics that the “China shock” (= Chinese imports replacing US manufacturing after China’s ascension to the WTO in 2001) was indeed a massive contributor to the hollowing out of America’s manufacturing base, and the decline of the rust belt, where Donald Trump enjoys massive voter support (Autor, Dorn, & Hanson, 2016).

The second Trump administration going after trade with Canada is a lot more surprising. Partly because these tariffs would be inflationary, and inflation was a major political issue in 2024, in a way that it was not at all in 2016; and partly because Canada is not China, in a number of ways that should really matter (more on this below).

In the following, I briefly lay out my own frame on the political motivations behind the tariff threats, and then outline six arguments for why I expect that we will see a return to normal relations more quickly than most observers seem to believe.

The first part on the political motivations behind the tariffs is there to frame the argument, but I don’t pretend to have any special professional insights there. My only slight edge might be that I am myself an American voter, so I do think about these things, but any reader can completely disagree with my opinion on the matter, and still follow me on the six reasons for why I expect a return to normalcy over the coming months.

So, with those caveats, here is my view of the politics behind the tariff threats.

The Political Rationale Behind Trump’s Trade Strategy

In the 2016 presidential election, trade with China and America’s manufacturing decline had merged into a single issue in the mind of many American voters. By the 2024 presidential election, this issue had expanded to include not just trade and manufacturing decline but also border policy, illegal immigration, and “deaths of despair,” of which fentanyl is a major driver, and which is hitting exactly the same places hit by the China shock (Case & Deaton, 2020).

There is a lot of political momentum behind all of these concerns and they form what in statistics is called a “principal component:” a group of issues that “move together.” A principal component shows the true data variation hidden behind a multitude of different data series. (For example, statistics on employment, labor force participation, unemployment and payroll are all separate data series, but they more or less reflect a single principal component that describes how the labor market is doing.) In American politics right now, trade, tariffs, border policy, manufacturing decline and fentanyl are a single principal component. Politically speaking, it’s all one thing.

A serviceable label for this principal component may be something like “economic nationalism (populism) vs neo-liberal globalism.”

This is weird to economists, and to civil servants in Ottawa and Washington DC, because on the surface, fentanyl and trade deficits have little to do with each other. Fentanyl and border security certainly weren’t mentioned in my trade econ textbooks in grad school. But to the unemployed manufacturing worker in Youngstown, Ohio, who lives surrounded by historically sky-high unemployment rates, experiences deaths of despair in their circle of friends and family, and sees that everything they buy at the local Walmart is made in China, the connection between these things feels obvious at a visceral level.

And this cluster of issues is one of the most core building blocks of what Donald Trump ran on in 2024. In fact, the incoming 2025 Trump administration is more committed to this principal component than the first Trump administration ever was.

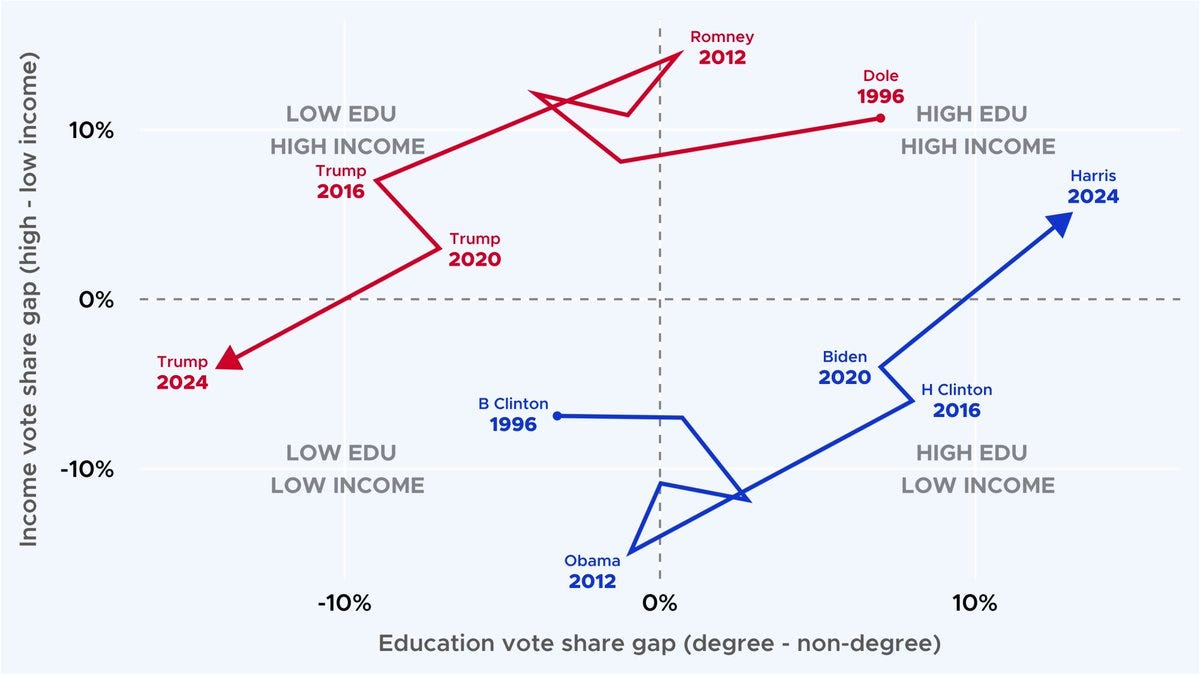

One way to see why that is is through the lens of who voted Republican in 2024, compared to the past. What the striking image below shows is a thirty-year migration of less educated and lower-income voters from the Democratic party to the Republican party (Ruffini, 2024).

(Source: Ruffini, P. 2024. https://www.patrickruffini.com/p/the-realignment-is-here)

This is essentially the political migration of those that were negatively affected by the twin forces of globalization and task-automation over the last 30 years.

This political migration is pretty ubiquitous across the OECD, because all countries have been hit with somewhat similar macro-forces of technology and globalization over the last thirty years. In my Native Germany, the AfD is being carried by exactly the same political sentiment as Donald Trump, and it is putting enormous pressure on Germany’s long-established political coalitions, which are quite likely to fracture after the upcoming federal elections on February 23rd.

Why the Tariffs Won’t Last: Six Key Arguments

My argument up to this point is simply that the current tariffs kerfuffle is about politics much more than it is about changing trade balances, about government revenue, or about benefiting the US economically. From this starting point of thinking of the tariff threat as an act of political symbolism, a way of making good on campaign promises, I will now give six reasons for my belief that we will arrive at a normalization of trade relations quicker than most observers seem to believe at the moment.

These reasons are:

-

Trump’s short-term negotiation style is based on short term disruption, but it is not what will drive trade-negotiations going into CUSMA’s renewal in July 2026

-

Trump’s economic advisors know that reducing trade deficits is not a recipe for growing income

-

Trump’s economic advisors know that the US cannot really reduce its trade deficits to begin with, because of something called the Triffen Dilemma

-

Imports from Canada do not contribute to the hollowing out of American manufacturing, in fact they are an important input into strengthening American manufacturing

-

Inflation is a real concern for US voters, possibly more so among Republican voters, and tariffs on Canada will be inflationary

-

Trade-relations with China are the real prize for the Trump administration, and his foreign policy advisors will view Canada as an important ally in going after this prize, more so given the prospect of a different Canadian government a few months from now

Argument #1: Negotiation Technique

At Ivey, my colleagues teach negotiation in a nuanced way that carefully considers the psychology of trust and reputation. As an economist, my own training in negotiations is limited to the frame of formal (and very mathy) game theory. But I think this limited frame actually works pretty well here. In game theory, repeat games usually force cooperation between negotiation partners, whereas in one-shot games, it’s all about bargaining power and threat points. In a one-shot game, an unreasonable party with an unreasonable threat point (perhaps willing to damage oneself in order to win) will shift the outcome in their favor. The more unreasonable the threat point, the more the compromise shifts. That means that In one-shot games, appearing unreasonable is a very reasonable thing to do, if you can pull it off. Donald Trump is great at pulling off the appearance of being unreasonable. His negotiation style thrives on disruption, bending the repeat-game nature of trade negotiations towards his favored one-shot negotiation style.

Medium term, however, I predict that the nature of the tariff negotiations will converge back to the norm, as we prepare for the renewal of CUSMA in July 2026.

Argument #2: The trade deficit drag argument is a fallacy

National income Accounting tells us that:

{GDP = Consumption + Investment + GovSpend + (Exports – Imports)}

(Exports – Imports) is the Balance of Trade and the Trade Deficit Drag fallacy is the idea that we can raise GDP on the left side by raising (Ex - Im) on the right side. It is a fallacy because the accounting makes it look true, but it doesn’t actually explain anything about where these numbers come from.

The fundamental macroeconomic insight that is being ignored is that trade deficits are usually not about trade. Instead, they are about money flows. When money flows into a country, that country’s currency strengthens, its exports become expensive and its imports become cheap, and it runs a trade deficit.

This argument is not exactly well understood among voters. For example, German and Japanese politicians and voters take great pride in their trade surpluses, and reinforce a narrative that trade surpluses are a sign of the great products produced in the country. The data suggests they are actually better explained by the bad investment climate in those countries. This is not really discussed much in public, but it is well understood by macro-economists, including I am sure the president’s economic advisors (from whom he would have already heard this during his first term).

Argument #3: The Triffen Dilemma makes it impossible for the US to run a trade surplus

Not only can the Trump administration not succeed at raising US GDP by turning a trade deficit into a trade surplus, it pretty much can’t even succeed at turning a trade deficit into a trade surplus in the first place. This is because the global economy is very much centered on the USD, and the USD is the world’s reserve currency. Global trade and global finance run on the USD. The world massively demands the USD as an asset and as collateral to keep on its balance sheets. In a US-centric global economy, this force completely overwhelms anything American consumers or producers do, making it pretty much impossible for the US to run a trade surplus.

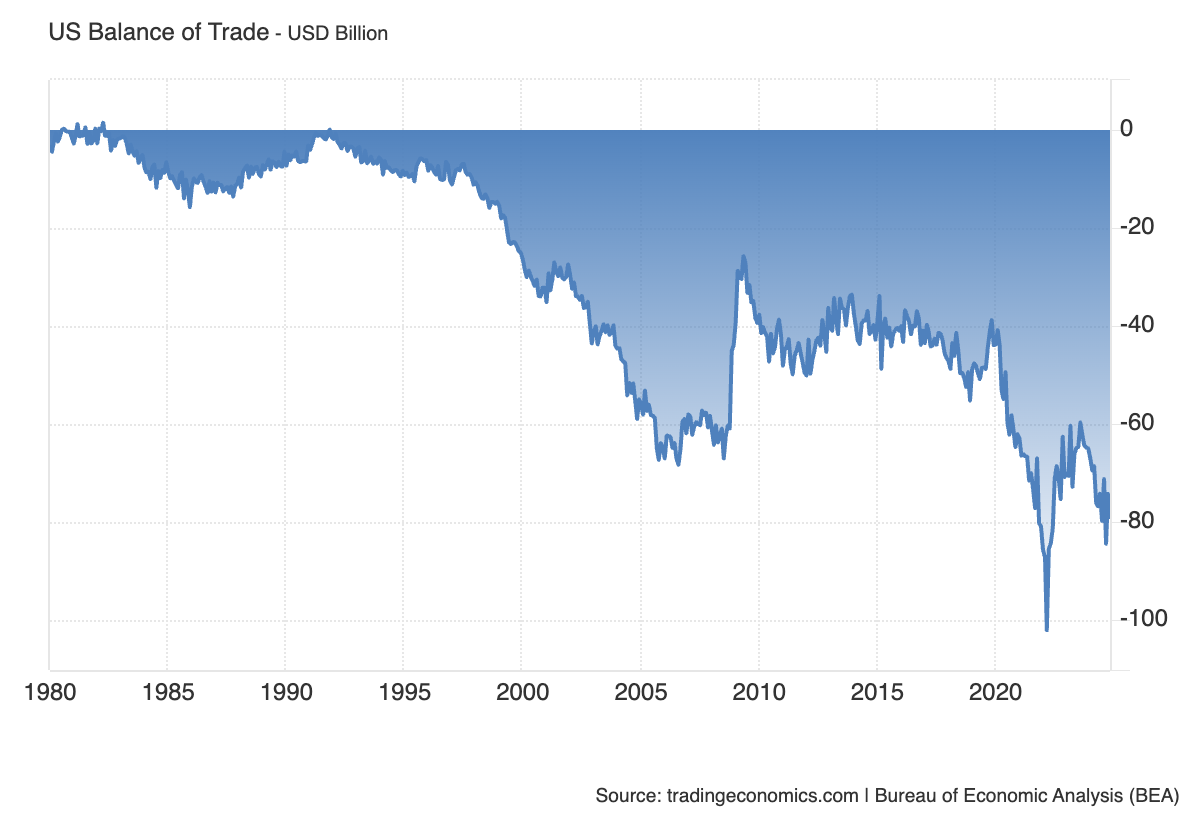

This is called the Triffen Dilemma: the world's dominant economy has no choice but to run trade deficits. This is more true the more globalized the world becomes, and the picture below shows how the US’ trade deficits deepened with the deepening of globalization after the fall of the Iron Curtain, and again after China’s accession to the WTO (Trading Economics, 2025).

Not only is the Triffen Dilemma not well understood among voters, it actually runs anathema to a political mythology that is dear to many voters’ hearts, which is that the US can have trade surpluses and also be the center of the global trading economy.

Regardless of whether they run counter to political beliefs however, the combination of Trade Deficit Drag Fallacy and Triffen Dilemma means that president Trump will naturally be forced to pivot away from the focus on tariffs because of the inherent futility of the endeavor of changing trade imbalances to benefit the US economy.

Argument #4: Canadian imports and American manufacturing

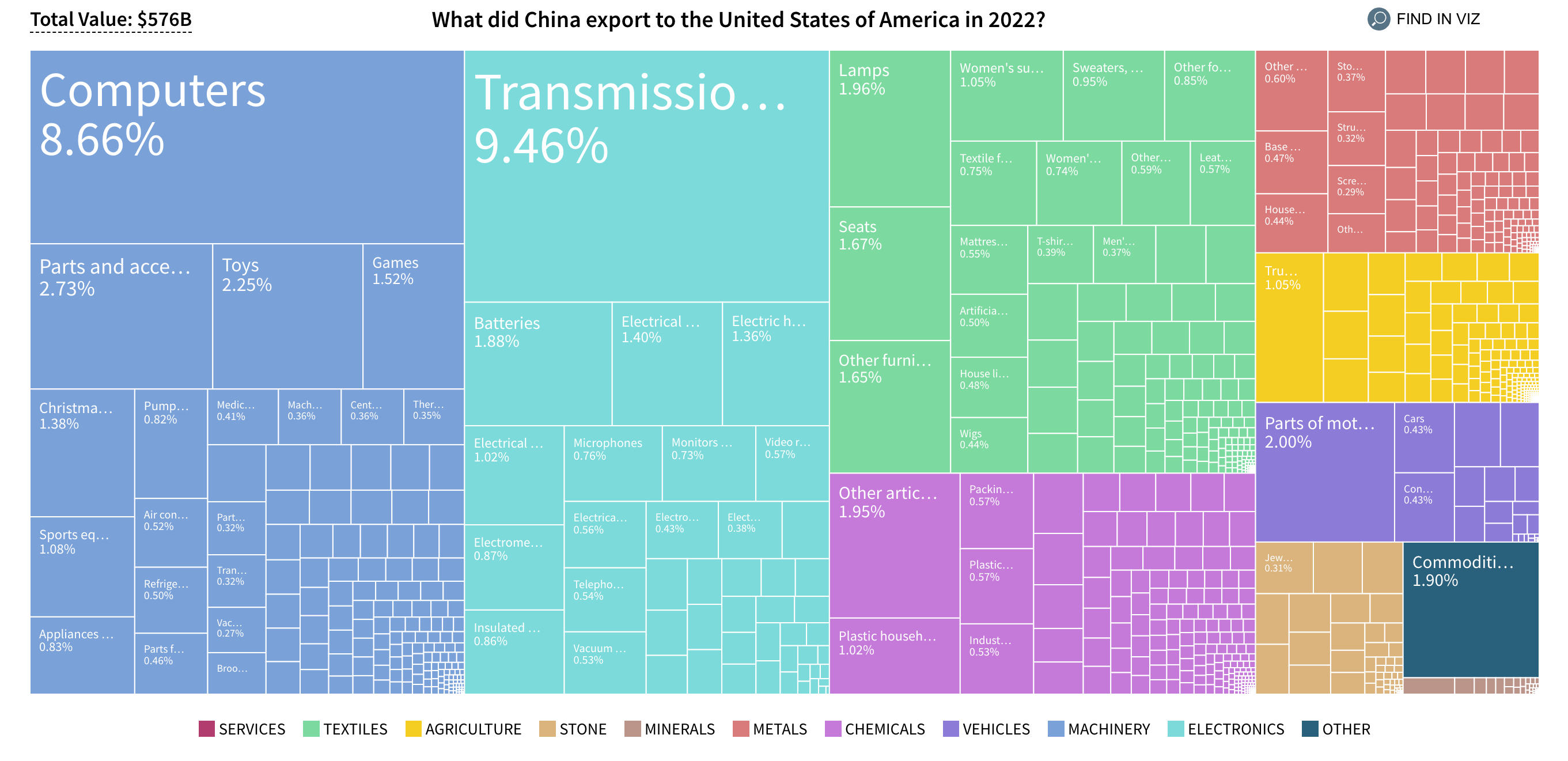

American Imports from China are mostly in finished products that before 2001 used to be made in America. This is apparent when we look at the composition of Chinese imports to the US in the image below (Harvard's Growth's Lab: Atlas of Economic Complexity).

(Source: Harvard's Growth's Lab: Atlas of Economic Complexity)

As such, the “China shock” is arguably responsible for much of the decline in American manufacturing, and it did the same to Canadian and German manufacturing.

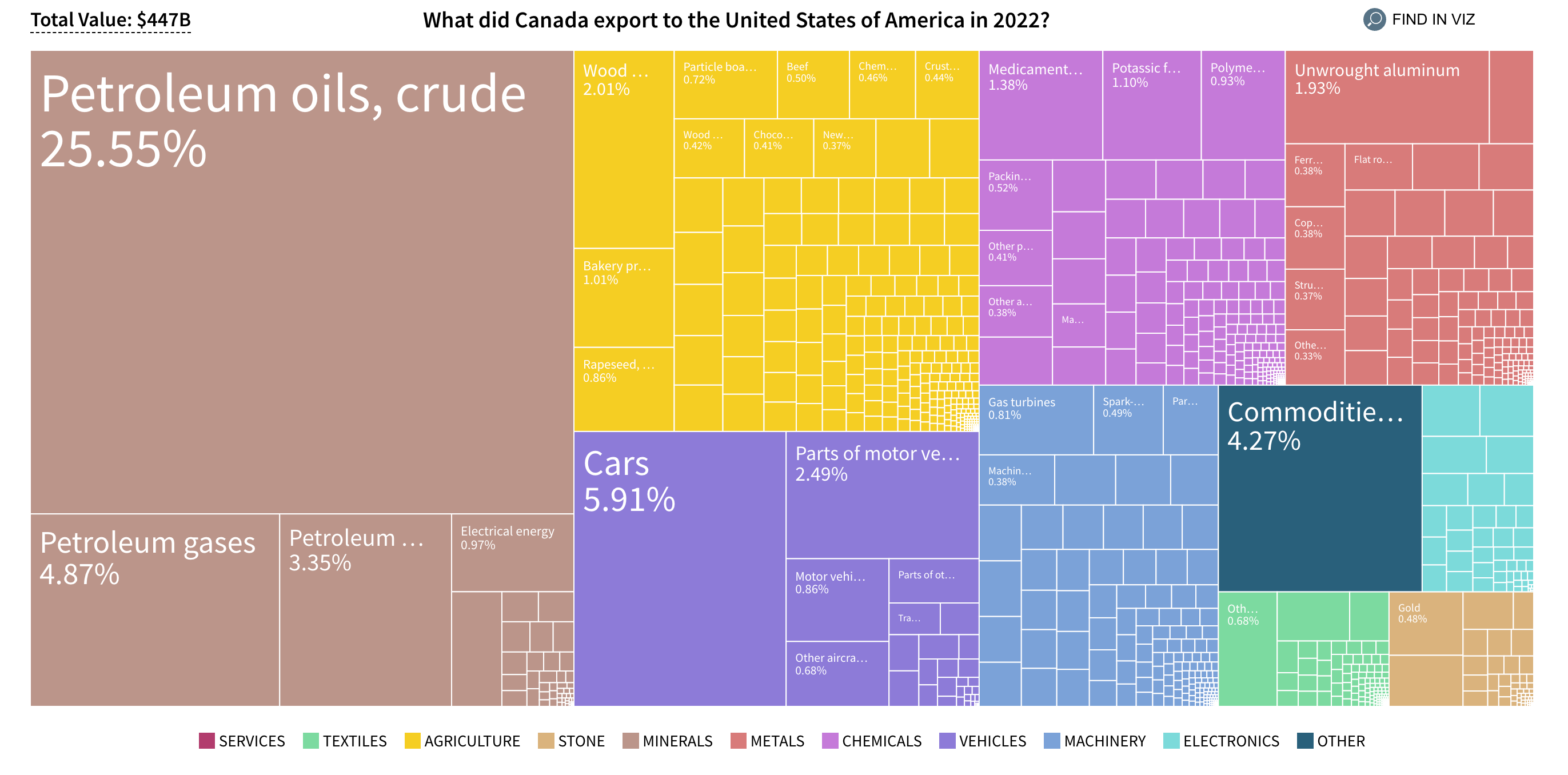

However, this is not at all true for US imports from Canada. Canada’s comparative advantage is in “growing stuff and in pulling stuff out of the ground”, and our exports reflect this, as they are mostly in oil and gas, agricultural commodities, and minerals.

(Source: Harvard's Growth's Lab: Atlas of Economic Complexity.)

(Source: Harvard's Growth's Lab: Atlas of Economic Complexity.)

This means Canadian imports are intermediate inputs into American manufacturing, and making these imports more expensive will actually undermine the Trump administration’s efforts at re-shoring supply chains.

Argument #5: Canadian imports and US inflation

This argument follows straight from the previous one. Taxing Canadian imports leads to clear cost increases for American manufacturers, food processors and oil refiners.

American manufacturers are sure to speak up publicly about cost increases caused by tariffs and they will pass these cost increases on to American consumers. American voters in 2025 are concerned about inflation in a way not seen since the 1980s (Hsu, 2025).

For this reason, I expect the political case for tariffs on Canadian products will have weakened a lot once the fog of war lifts.

Argument #6: US-Canadian relations

Another reason to be less worried is political change in Canada.

Trudeau and Trump were always going to be somewhat at odds on basic policy direction. In contrast, while Poilievre has carefully avoided the political trap of aligning himself closely with Trump, it does seem pretty clear that a future Poilievre government would be on better terms politically with the Trump administration than a Liberal government could be. And this might have important repercussions for US-Canadian trade relations.

The Trudeau government never seemed at peace with the idea that Canada’s comparative advantage is growing stuff and in pulling stuff out of the ground. In contrast, a future Poilievre government is more likely to lean into this comparative advantage, making it a natural strategic ally to the Trump administration’s efforts at reshoring US manufacturing. Interestingly, even the current government may be leaning into this argument now, going by Minister Wilkinson’s latest remarks on US-Canada relations (Atlantic Council, 2025).

A Temporary Disruption, Not a Lasting Policy Shift

In combination, these six arguments strongly suggest to me that we should expect a normalization of US-Canada trade relations relatively soon, and that we’ll be back to normal by the time CUSMA negotiations pick up in earnest.

References

Atlantic Council. (2025, February 4). Canadian Energy Minister Jonathan Wilkinson on US-Canada energy cooperation. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/event/canadian-energy-minister-jonathan-wilkinson-on-us-canada-energy-cooperation/

Autor, D. H., Dorn, D., & Hanson, G. H. (2016). The China shock: Learning from labour market adjustment (NBER Working Paper No. 21906). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w21906

Case, A., & Deaton, A. (2020, April 15). How deaths of despair are tearing America apart. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2020/4/15/21214734/deaths-of-despair-coronavirus-covid-19-angus-deaton-anne-case-americans-deaths

Harvard’s Growth Lab. (n.d.). Canada's export composition to the United States. The Atlas of Economic Complexity. Retrieved February 18, 2025, from https://atlas.hks.harvard.edu/explore/treemap?exporter=country-124&importer=country-840

Hsu, J. W. (2025, February 11). The mood of the American consumer is souring. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/economy/consumers/americans-jittery-over-inflation-university-of-michigan-survey-suggests-1476cf39

Ruffini, P. (2024, November 15). The realignment is here. The Intersection. https://www.patrickruffini.com/p/the-realignment-is-here

Trading Economics. (2025, January). United States balance of trade. https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/balance-of-trade

About the Author

Christian Dippel holds the Donald F. Hunter Professorship in International Business at Ivey Business School and serves as an LNC Faculty Fellow. His expertise lies in non-market strategy, governance, and Indigenous economic development.