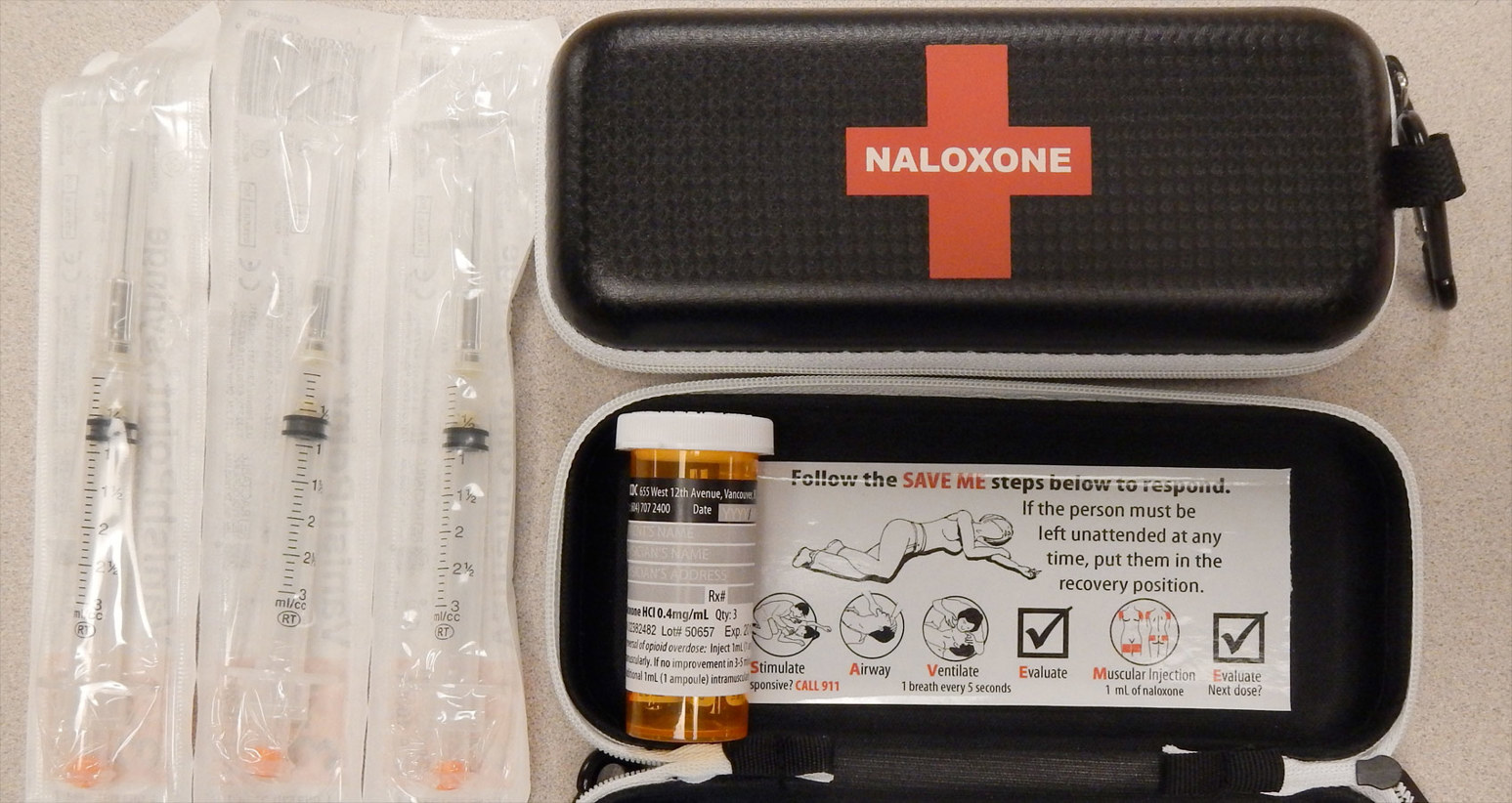

In the midst of a national opioid crisis, some Canadian school boards have implemented school-based naloxone programs in order to provide secondary school administrators, teachers and students with access to naloxone kits, which can reverse an opioid overdose.

Recognizing that school boards have limited budgets for public health interventions, researchers at Western University’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry and the Ivey Business School have used the principles of cost-effectiveness in order to determine whether or not naloxone programs are the best use of resources.

“We created this tool, not because the program is costly, but because targeting overdose fatality prevention for a low-risk population has an unclear value,” said Lauren Cipriano, PhD, who co-authored the study with Gregory Zaric, PhD, both cross-appointed in Schulich Medicine & Dentistry and Ivey. “The Public Health Agency of Canada reports that there were 80 overdose fatalities in 2017 for people under the age of 19, but there are no public reports of opioid overdoses, fatal or otherwise, happening in a school.”

The cost-effectiveness examination was published in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence and used the Toronto District School Board as an example. The study evaluated costs and health effects of naloxone programs relative to relying on existing emergency and public health resources alone.

The study determined that in order for the naloxone program to be cost-effective, there would need to be at least one overdose per year across the whole school board (112 high schools), and they would need to reduce mortality by about 50 per cent (from about 10 per cent to 5 per cent).

One goal of this research is that any school board could use the spreadsheet tool to determine whether a naloxone program is cost-effective for their particular circumstances. The researchers have made their evaluation tool publicly available through the journal’s web site.

“Each school board can tailor the inputs for their own situation. They may decide to put naloxone kits in high schools anyway, but I would hope that they would do so informed by solid evidence,” said Zaric.

The researchers argue that if the risk of an overdose in a high school is low, then other programs aimed at improving the health and wellbeing of students may be better use of limited resources.

“Because the budget for a school board is limited, it is about using that limited budget in the best possible way,” said Zaric. “There are a lot of public health interventions for high school students around mental health, diet, and sex education that might have a better incremental cost per health benefit or per quality of life years gained.”